What to do when you buy a fake Japanese woodblock print at auction

New technology continues to push collectors to internet platforms when bidding at auction. Unlike the recent past, when bidding was limited primarily to those who previewed and attended sales in person, today the majority of action is on the computer. While it is still possible to preview sales in person, the overwhelming majority of bidders do not and must rely on jpg images that often fail to show the complete print, lack clarity or fail to reveal defects. Many auctions also lack expertise and vaguely or incorrectly describe their Japanese woodblocks. As a result, buyers sometimes are badly disappointed with their purchases. This blog explores how to avoid such disappointment and what to do if you buy a fake. The same advice holds for artwork with a misleading or incorrect description.

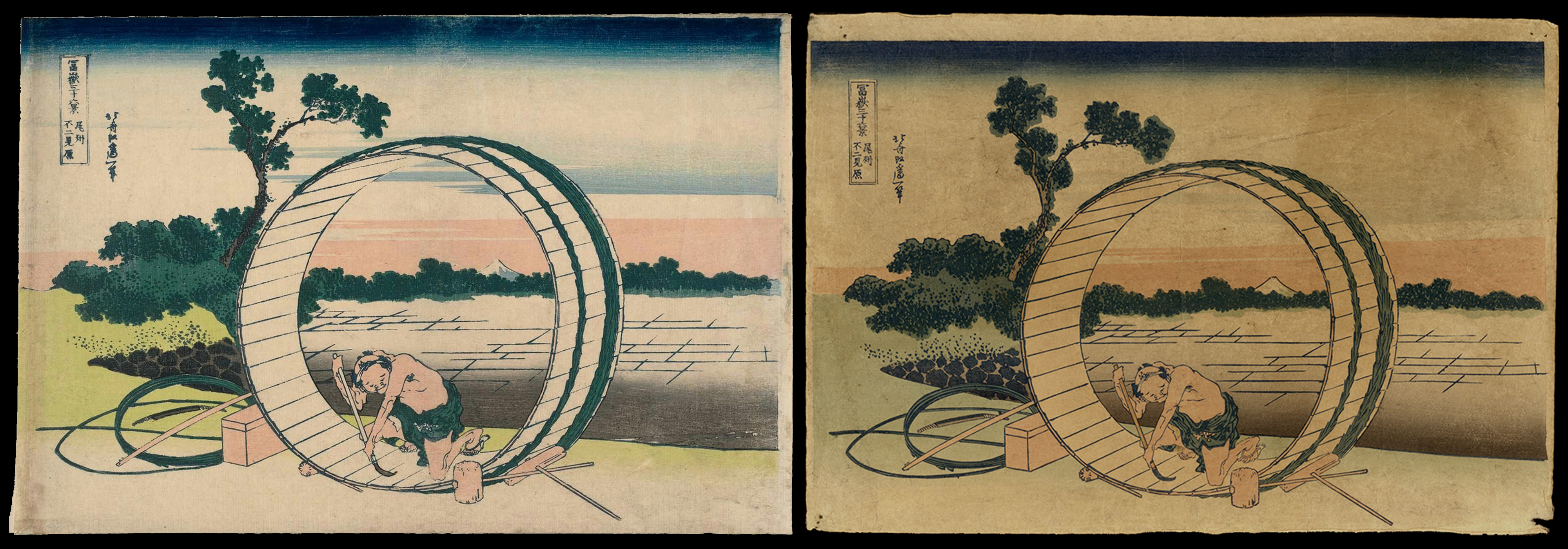

The first step is to ask questions before the sale. If you need a condition report, ask. If you need more or better pictures, ask. If you don’t get a response, ask again. Ask by email and ask by phone. Some auctions are reluctant to remove prints from frames, either because they lack the permission of their consignor or they worry about damaging the print. Take this uncertainty into account when you bid. Even when you have great images to study, the risk remains that they are photo-mechanical copies indistinguishable from an original, especially when framed. The best protection against such a surprise is to ask directly about the nature of the work. The language used to describe the print is also instructive. If the auction describes it as a “woodblock” or “woodcut”, and the print is a photo-mechanical copy, the description is clearly wrong. If it describes the work more generally as a “print,” you are at risk. Also look at the estimate. You are more likely to recover for buying a fake estimated for thousands of dollars than you are for one estimated for ten.

In general, auctions are run by honest businessmen and women who do not want to cheat you. They solicit far flung participation over the internet, often international, and in exchange, their rules over returns have been loosened. Remember, though, that auctioneers must balance protecting the interests of the consignor against those of the buyer. If you have a problem, contact the auctioneer immediately. Once the consignor has been paid, the likelihood that you can recover your costs drops to about zero. Avoid confrontation or an adversarial approach. Many auctions require bidders to agree to language acknowledging that no returns are accepted, so they start with a leg up. If there is a problem, do not expect the auctioneer to take your word for it. You will need to find a bona fide expert to back up your view of the print, the sooner, the better. Exactly how much expertise is needed may vary. You may need a written attestation from a dealer, a scholar, the original artist or a body (or person) that authenticates the works of a particular artist. In the end you may still feel like Dorothy in the Wizard of Oz when she returns with the witch’s broomstick only to be turned away. Buyer beware may still rule with some. But if you do your prep work and if you demonstrate beyond a doubt that you bought a fake, chances are good that you can return the dud, even if the auction policy states no returns.

Of course, the best way to avoid the grief of returning fakes is to do business with auctions that guarantee the authenticity of their works and have the expertise to back up the guaranty, like Floating World Auctions.